编者按:

尽管某些益生菌已经被证明或可预防、治疗一些特定疾病或状况,但是其背后所依据的研究质量参差不齐。食品、保健食品(膳食补充剂)、特医食品属性的益生菌与药物不同,它们受到的监管较为宽松。因此,益生菌市场在蓬勃发展的同时,也出现了不少“乱象”。

那么,我们究竟如何选择益生菌产品呢?下单前应该考虑哪些因素呢?

今天,我们特别编译国际益生菌和益生元科学协会成员 Mary Ellen Sanders 等人最近发表的文章。该文总结了美国益生菌市场的政府监管、科学循证的情况,阐述了不少关于益生菌产品选择与使用的建议,希望能为相关的产业人士和读者带来一些启发和帮助。

微生物组时代下:“益生菌乱象”

我们身处在一个微生物组的时代。不管是大众新闻还是科学新闻,都在强调微生物组对我们身体健康的重要性,即便这些媒体可能并不知道如何调节与不同疾病或者亚健康状态相关的肠道菌群结构。

其中一种可能用于调节肠道菌群的手段是使用益生菌。益生菌被定义为“摄入一定量后,能够对宿主产生健康益处的活的微生物”[1]。

某些益生菌已被证明能够预防和治疗肠内外的特定疾病或改善不良状况。但是,这些依据的研究水平和质量大相径庭。

除此之外,政府监管部门批准的健康声称里的概念也被认为是割裂、复杂、缺乏一惯性的,比如食品 VS 药物、维持健康 VS 治疗疾病、新兴的证据 VS 科学界的共识[2]。这也造成了医患双方的混乱,他们对是否能够相信产品标签上的声称产生了困惑。

一般来说,如果病人需要一款能够帮助他解决某一特定症状的产品时,医生仅仅告诉、推荐病人“可以使用益生菌”并不是特别有意义。

在美国市场上,迄今为止益生菌都还没有作为药物售卖,尽管如此,临床医生仍然可以基于已有的证据来推荐它们。

在本文中,我们将回顾益生菌产品有效治疗某些特定疾病/状况的研究,讨论益生菌的功能性和安全性,并提供一些益生菌监管标准的相关信息,还将基于现有的依据对益生菌的使用给出一些建议和指导。

益生菌的监管和商业化

在美国,益生菌作为膳食补充剂、特医食品或普通食品售卖,与药物相比,这些类别的产品仅需要较低水平的证据,也拥有较为宽松的监管。

虽然也存在某些益生菌在治疗或预防某些特定疾病或状况时的效果,即使没有传统药物干预的效果那般好,但是也与之相似(表 1)[3-32]。然而,不同于药物的是,所有药物在上市前都会受到严格的监管,但是益生菌市场上的产品所依据的证据水平却是参差不齐的——从被充分证实的,到证据十分有限的都存在。

尽管目前益生菌还没有作为非处方药或处方药在美国销售,但是益生菌药物最终可能会进入市场。那么,在益生菌尚未作为药物进入市场的情况下,我们应该如何选购益生菌产品呢?

推荐产品时需要考虑什么

需要记住的是,就益生菌而言,菌株、剂量和适应症说明等都很重要。

正如我们所知道的,不是所有的抗生素都对一切感染都同样有效,同样的,益生菌的有效性针对不同的情况可能也会出现差异,事实上,这些差异经常出现。使用效果在病患之间还会存在个体差异。

此外,在一些案例中,可能有不止一种益生菌具有效果,这可能是因为这些益生菌菌株存在相同或相似的潜在作用机制。比如,大部分益生菌都会在结肠内产生短链脂肪酸,这是支持消化健康的一个共同机制[33~35]。

与倾向于高剂量或大量菌株的建议不同36,我们的建议是采用在临床试验中被证实有效的水平,因此这可能会是一天 1 亿 CFU(最常见的益生菌产品活菌数量单位)的低摄入量[37,38]。

理解益生菌产品标签是一个好的开始

美国益生菌膳食补充剂的标签被要求应涵盖产品中包含的种属和菌株信息、货架期内活菌剂量和预计功效。

(作者注:为了更好地理解这些标签,可以在网站 https://isappscience.org/ infographics/probiotic-labelling 查阅由国际益生菌和益生元国际科学协会发布的标签图解[40]。)

根据联合国粮食及农业组织(FAO)和世界卫生组织(WTO)的指导方针,所有的益生菌产品都应在产品包装上明确展示出上述信息[41]。

但是,一些益生菌产品展示的信息可能并不全,例如,它们可能不会详细说明产品中的菌株或是推荐的剂量水平。这些产品标签中缺失的细节可能会展示在产品网站上,也可能没有。由于缺乏这些信息,可能就难以对这些产品提出基于证据的建议。

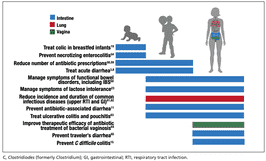

表1.有良好证据支持的常用益生菌

益生菌通常是安全的,但也有警告

经典的益生菌(Lactobacillus spp,Bifidobacterium spp 和 Saccharomyces cerevisiae var. boulardii)的整体安全性已经经过较好的论证[42,43]。

在美国,许多益生菌菌株通常被认为可以安全地在食品中使用[44,45]。欧洲食品安全委员会(类似 FDA,只管辖食品,不包括药物)也已经评估了许多传统种类的益生菌,这些益生菌在欧盟也被认为可以安全应用于食品中。

但是请注意,通过膳食补充剂和食物来摄入的益生菌是针对大众人群而非病患群体的。因此,生产商们不需要确保产品在弱势群体中的安全性。

然而,益生菌往往在医院药房也有供应[46,47]。一个专家小组已经评估了益生菌在病患群体中的使用情况,提出了用于治疗和预防疾病的微生物产品需要质量保证的观点。

专家推荐健康保健专业人士(包括药剂师和内科医生)应当向生产商索要质量信息,而参与其中的生产商应当提供益生菌产品的第三方检验来确保产品达到了可应用的纯度标准[48,49]。

已发表的病例研究已经报道,益生菌的使用可能是败血症的一个罕见原因[43]。最近发现 Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG 与 6 个病危患者的菌血症相关,但是这些患者的所有症状都已消退,没有并发症[50]。

另外,一名早产婴儿的死亡被发现与受到机会性病原霉菌污染的益生菌摄入有关[51]。

一项关于多种益生菌在病危胰腺炎患者中应用的随机对照试验(RCT)表明,给予多种益生菌的组别出现了更高的死亡率[52]。但是,进一步的数据检查表明,观察到的死亡率增加是由于病情严重程度和其他问题导致的,而非益生菌[53]。

益生菌已经被越来越高频地被用于高危病患人群,包括早产婴儿、癌症病人和病危病人,但是口服摄入益生菌的负面作用并未出现显著性增加[54~56]。

综合来说,相比于益生菌组别,临床研究报道更多的是安慰剂组别出现不利影响[42]。通过对这些研究中收集到的感染数据的分析,证明在一些情况下,特定的益生菌确实能降低感染的风险。

一个值得注意的案例是纳入了 37 个随机对照试验的荟萃分析,该分析表明益生菌降低了早产儿发生迟发性新生儿败血症的机率[57]。

目前,尽管使用益生菌的风险低,但是仍然需要警惕,特别是在特定情况下的风险,如在特别虚弱的患者身上的应用,或者只有有限安全性数据的产品,这些都尚待研究。

推荐、购买的任何产品都应在符合相应监管标准条件下生产,专业保健人士最好能够自主进行质量审核来保证质量[49]。

图1. 来自临床试验的系统综述和荟萃分析支持在某些情况下使用益生菌。

如何应用益生菌

人们已经研究了益生菌在许多疾病中的临床益处(图 1)[2,8,11,15,19,23,54,58~65],对于临床试验的系统性回顾表明,即便一些临床试验质量很低,但是整体的结果依然能充分作为支撑推荐益生菌的论据[66]。

不过,一些证据可能需要验证性研究来阐明应当推荐哪个特定产品。

益生菌可能不仅可以解决肠道问题,也可以解决非肠道的问题,并在整个生命过程中发挥不同的功能。

表 1 中[3-32],我们总结了益生菌在初级保健医学中广泛应用的良好证据。

我们提供的数据或许有助于形成一些针对特定适应症的产品建议。许多益生菌都已经在胃肠道亚健康对象中进行了测试,包括与肠道功能相关的症状,从偶尔的排气、腹胀或便秘,到未被诊断的肠易激综合征(IBS)。

像 Bifidobacterium infantis subsp. longum 35624(Align 品牌中的益生菌),Lactobacillus plantarum 299V(在 Nature Made 品牌的 Digestive Probiotic Daily Balance 中的菌株),以及像达能集团的 Activia 酸奶、养乐多的发酵乳或 Good Belly 的果汁,或许都可以被推荐用于缓解消化症状。

对于经受着与诊断疾病不相关的肠道症状的病患来说,尝试一种有文献支撑的菌株 3~4 周是合理的。

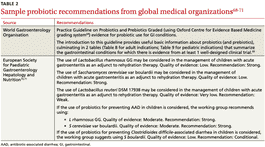

虽然现在我们很难提前预测某种益生菌是否会有效,但随着我们对个体微生物组、饮食、遗传学对机体应对特定益生菌的反应的影响的认知越来越深入,这一切可能会马上发生改变。表 2 列出了一些国际专家委员会精选的研究中的推荐案例[68~71]。

今天的主流媒体普遍建议摄入更多的发酵食品。尽管我们大体上认同这种推荐,但是临床医生应当清楚发酵食品不等于活的微生物的来源,因为不是所有的发酵食品都含有活的微生物。而且,很多发酵食品缺乏支持具有保健功能的依据,也不是益生菌的来源。

如果患者的目的是采取一个含有活菌的日常饮食,那么可能任何数量的益生菌产品和含有活菌的发酵食品都足够发挥作用。但是,当患者需要益生菌来满足特定需求,就应该基于特定产品的现有研究依据来给出建议。

表2.国际专家委员推荐的益生菌案例

未来展望

益生菌领域的基础研究、临床实验和市场发展都进展迅速。虽然目前被研究的益生菌大多来自 Lactobacillus、Bifidobacterium 和 Saccharomyces。但是,益生菌的潜力激励了更多人去探索健康人体肠道中未被开发挖掘的的微生物。像 Akkermansia,Faecalibacterium 和 Rosburia 这样的微生物都可能会成为“下一代益生菌”,甚至可能会被开发为药物[72]。

具有前景的研究热点,包括微生物组相关的棘手病症,比如代谢综合征(肥胖、糖尿病和脂质调节异常)和大脑功能障碍(抑郁、焦虑、认知、自闭症)。

现在看来,益生菌还会接着被广泛应用,我们希望是以一个更为基于实证的方式。随着我们对微生物组的个体差异了解得越来越多,给出的建议也可能会越发地对病患具有针对性。

虽然有充分证据的益生菌应该被优先推荐,但是鉴于传统益生菌(比如 Lactobacillus,Bifidobacterium 和 Saccharomyces 等菌株)的风险较低,所以有时候可能也可被允许用于试验。

参考文献:

1.Hill C, Guarner F, Reid G, et al. Expert consensus document. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;11:506-514.

2.Sanders ME, Heimbach JT, Pot B, et al. Health claims sub- stantiation for probiotic and prebiotic products. Gut Microbes. 2011;2:127-133.

3.Feizizadeh S, Salehi-Abargouei A, Akbari V. Efficacy and safety of Saccharomyces boulardii for acute diarrhea. Pediatrics. 2014;134:e176-e191.

4.Francavilla R, Lionetti E, Castellaneta S, et al. Randomised clini- cal trial: Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 17938 vs. placebo in children with acute diarrhoea—a double-blind study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36:363-369.

5.Dinleyici EC, Dalgic N, Guven S, et al. Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 17938 shortens acute infectious diarrhea in a pediatric outpatient setting. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2015;91:392-396.

6.Dinleyici EC, Group PS, Vandenplas Y. Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 17938 effectively reduces the duration of acute diarrhoea in hos- pitalised children. Acta Paediatr. 2014;103:e300-e305.

7.Urbanska M, Gieruszczak-Bialek D, Szajewska H. Systematic review with meta-analysis: Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 17938 for diarrhoeal diseases in children. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;43:1025-1034.

8.Szajewska H, Ko?odziej M, Gieruszczak-Bia?ek D, et al. System- atic review with meta-analysis: Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG for treating acute gastroenteritis in children—a 2019 update. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;49:1376-1384.

9.Vanderhoof JA, Whitney DB, Antonson DL, et al. Lactobacillus GG in the prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhea in chil- dren. J Pediatr. 1999;135:564-568.

10.Szajewska H, Albrecht P, Topczewska-Cabanek A. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial: effect of Lactobacillus GG supplementation on Helicobacter pylori eradication rates and side effects during treatment in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;48:431-436.

11.Guo Q, Goldenberg JZ, Humphrey C, et al. Probiotics for the pre- vention of pediatric antibiotic-associated diarrhea. Cochrane Da- tabase Syst Rev. 2019;4:CD004827.

12.Arvola T, Laiho K, Torkkeli S, et al. Prophylactic Lactobacillus GG reduces antibiotic-associated diarrhea in children with respira- tory infections: a randomized study. Pediatrics. 1999;104:e64.

13.Szajewska H, Kolodziej M. Systematic review with meta-analysis: Saccharomyces boulardii in the prevention of antibiotic-associat- ed diarrhoea. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42:793-801.

14.Hickson M, D’Souza AL, Muthu N, et al. Use of probiotic Lacto- bacillus preparation to prevent diarrhoea associated with anti- biotics: randomised double blind placebo controlled trial. BMJ. 2007;335:80.

15.Goldenberg JZ, Yap C, Lytvyn L, et al. Probiotics for the preven- tion of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in adults and children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;(12):CD006095.

16.Beausoleil M, Fortier N, Gue?nette S, et al. Effect of a fermented milk combining Lactobacillus acidophilus Cl1285 and Lactoba- cillus casei in the prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhea: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Can J Gas- troenterol. 2007;21:732-736.

17.Sampalis J, Psaradellis E, Rampakakis E. Efficacy of BIO K+ CL1285 in the reduction of antibiotic-associated diarrhea— a placebo controlled double-blind randomized, multi-center study. Arch Med Sci. 2010;6:56-64.

18.Gao XW, Mubasher M, Fang CY, et al. Dose-response efficacy of a proprietary probiotic formula of Lactobacillus acidophilus CL1285 and Lactobacillus casei LBC80R for antibiotic-associated diarrhea and Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea prophy- laxis in adult patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1636-1641.

19.Sung V, D’Amico F, Cabana MD, et al. Lactobacillus reuteri to treat infant colic: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2018;141. pii: e20171811.

20.Eskesen D, Jespersen L, Michelsen B, et al. Effect of the probiotic strain Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis, BB-12(R), on def- ecation frequency in healthy subjects with low defecation fre- quency and abdominal discomfort: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trial. Br J Nutr. 2015;114:1638- 1646.

21.Yang YX, He M, Hu G, et al. Effect of a fermented milk contain- ing Bifidobacterium lactis DN-173010 on Chinese constipated women. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:6237-6243.

22.Kolars JC, Levitt MD, Aouji M, et al. Yogurt—an autodigesting source of lactose. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:1-3.

23.Savaiano DA. Lactose digestion from yogurt: mechanism and rel- evance. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99(5 suppl):1251S-1255S.

24.EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products Nutrition and Allergy. Scientific Opinion on the substantiation of health claims related to live yo- ghurt cultures and improved lactose digestion (ID 1143, 2976) pursuant to Article 13(1) of Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006. EFSA Journal. 2010;8(10):1763.

25.Martinez RC, Franceschini SA, Patta MC, et al. Improved cure of bacterial vaginosis with single dose of tinidazole (2 g), Lactobacil- lus rhamnosus GR-1, and Lactobacillus reuteri RC-14: a random- ized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Can J Microbiol. 2009;55:133-138.

26.Anukam K, Osazuwa E, Ahonkhai I, et al. Augmentation of anti- microbial metronidazole therapy of bacterial vaginosis with oral probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus GR-1 and Lactobacillus reuteri RC-14: randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. Mi- crobes Infect. 2006;8:1450-1454.

27.Szajewska H, Ruszczynski M, Radzikowski A. Probiotics in the pre- vention of antibiotic-associated diarrhea in children: a meta-analy- sis of randomized controlled trials. J Pediatr. 2006;149:367-372.

28.Kyriakos N, Papamichael K, Roussos A, et al. A lyophilized form of Saccharomyces boulardii enhances the Helicobacter pylori eradication rates of omeprazole-triple therapy in patients with peptic ulcer disease or functional dyspepsia. Hospital Chronicles. 2013;8:127-133.

29.Lewis SJ, Potts LF, Barry RE. The lack of therapeutic effect of Sac- charomyces boulardii in the prevention of antibiotic-related diar- rhoea in elderly patients. J Infect. 1998;36:171-174.

30.Auclair J, Frappier M, Millette M. Lactobacillus acidophilus CL1285, Lactobacillus casei LBC80R, and Lactobacillus rhamno- sus CLR2 (Bio-K+): characterization, manufacture, mechanisms of action, and quality control of a specific probiotic combination for primary prevention of Clostridium difficile infection. Clin In- fect Dis. 2015;60(Suppl 2):S135-S143.

31.Maziade PJ, Pereira P, Goldstein EJ. A decade of experience in pri- mary prevention of Clostridium difficile infection at a community hospital using the probiotic combination Lactobacillus acidophi- lus CL1285, Lactobacillus casei LBC80R, and Lactobacillus rham- nosus CLR2 (Bio-K+). Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(Suppl 2):S144-S147.

32.FDA. Guidance for industry on irritable bowel syndrome-clinical evaluation of drugs for treatment. 2012. www.federalregister.gov/ documents/2012/05/31/2012-13143/guidance-for-industry- on-irritable-bowel-syndrome-clinical-evaluation-of-drugs-for- treatment. Accessed March 25, 2020.

33.Binder HJ. Role of colonic short-chain fatty acid transport in diar- rhea. Annu Rev Physiol. 2010;72:297-313.

34.Kim HK, Rutten NB, Besseling-van der Vaart I, et al. Probiotic sup- plementation influences faecal short chain fatty acids in infants at high risk for eczema. Benef Microbes. 2015;6:783-790.

35.Surendran Nair M, Amalaradjou MA, Venkitanarayanan K. Anti- virulence properties of probiotics in combating microbial patho- genesis. Adv Appl Microbiol. 2017;98:1-29.

36.Wilkins T, Sequoia J. Probiotics for gastrointestinal conditions: a summary of the evidence. Am Fam Physician. 2017;96:170-178.

37.Urbanska M, Szajewska H. The efficacy of Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 17938 in infants and children: a review of the current evi- dence. Eur J Pediatr. 2014;173:1327-1337.

38.Whorwell PJ, Altringer L, Morel J, et al. Efficacy of an encapsu- lated probiotic Bifidobacterium infantis 35624 in women with ir- ritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1581-1590.

39.Merenstein D, Guzzi J, Sanders ME. More information needed on probiotic supplement product labels. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34:2735-2737.

40.International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiot- ics. Deciphering a probiotic label. https://isappscience.org/ infographics/probiotic-labelling/. Accessed March 25, 2020.

41.Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations and World Health Organization. Guidelines for the evaluation of pro- biotics in food. 2002. www.who.int/foodsafety/fs_management/ en/probiotic_guidelines.pdf. Accessed March 25, 2020.

42.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Safety of probiotics to reduce risk and prevent or treat disease. AHRQ Publication No. 11-E007. 2011. www.ahrq.gov/downloads/pub/evidence/pdf/ probiotics/probiotics.pdf. Accessed March 25, 2020.

43.Sanders ME, Akkermans LM, Haller D, et al. Safety assessment of probiotics for human use. Gut Microbes. 2010;1:164-185.

44.European Food Safety Authority. Statement on the update of the list of QPS-recommended biological agents intentionally added to food or feed as notified to EFSA. 2: Suitability of taxonomic units notified to EFSA until March 2015. EFSA J. 2015;12:4138.

45.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) Notification Program. 2020. www.fda.gov/ animalveterinary/products/animalfoodfeeds/generallyrecognized assafegrasnotifications/default.htm. Accessed March 25, 2020.

46.Yi SH, Jernigan JA, McDonald LC. Prevalence of probiotic use among inpatients: a descriptive study of 145 U.S. hospitals. Am J Infect Control. 2016;44:548-553.

47.Abe AM, Gregory PJ, Hein DJ, et al. Survey and systematic litera- ture review of probiotics stocked in academic medical centers within the United States. Hosp Pharm. 2013;48:834-847.

48.Sanders ME, Merenstein DJ, Ouwehand AC, et al. Probiotic use in at-risk populations. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2016;56:680-686.

49.Jackson SA, Shoeni JL, Vegge C, et al. Improving end-user trust in the quality of commercial probiotic products. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:739.

50.Yelin I, Flett KB, Merakou C, et al. Genomic and epidemiologi- cal evidence of bacterial transmission from probiotic capsule to blood in ICU patients. Nat Med. 2019;25:1728-1732.

51.Vallabhaneni S, Walker TA, Lockhart SR, et al. Notes from the field: fatal gastrointestinal mucormycosis in a premature infant associated with a contaminated dietary supplement—Connecti- cut, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:155-156.

52.Besselink MG, van Santvoort HC, Buskens E, et al. Probiotic prophylaxis in predicted severe acute pancreatitis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;371: 651-659.

53.van den Nieuwboer M, Claassen E. Dealing with the remaining controversies of probiotic safety. Benef Microbes. 2019;27:1-12.

54.AlFaleh K, Anabrees J. Probiotics for prevention of necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(4):CD005496.

55.Redman MG, Ward EJ, Phillips RS. The efficacy and safety of pro- biotics in people with cancer: a systematic review. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:1919-1929.

56.Liu KX, Zhu YG, Zhang J, et al. Probiotics’ effects on the incidence of nosocomial pneumonia in critically ill patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2012;16:R109.

57.Rao SC, Athalye-Jape GK, Deshpande GC, et al. Probiotic supple- mentation and late-onset sepsis in preterm infants: a meta-anal- ysis. Pediatrics. 2016;137:e20153684.

58.King S, Tancredi D, Lenoir-Wijnkoop I, et al. Does probiotic con- sumption reduce antibiotic utilization for common acute infec- tions? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Public Health. 2019;29:494-499.

59.Scott AM, Clark J, Julien B, et al. Probiotics for preventing acute otitis media in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;(6):CD012941.

60.Niu HL, Xiao JY. The efficacy and safety of probiotics in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: evidence based on 35 randomized controlled trials. Int J Surg. 2020;75:116-127.

61.King S, Glanville J, Sanders ME, et al. Effectiveness of probiotics on the duration of illness in healthy children and adults who de- velop common acute respiratory infectious conditions: a system- atic review and meta-analysis. Br J Nutr. 2014;112:41-54.

62.Hao Q, Dong BR, Wu T. Probiotics for preventing acute up- per respiratory tract infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(2):CD006895.

63.Mardini HE, Grigorian AY. Probiotic mix VSL#3 is effective ad- junctive therapy for mild to moderately active ulcerative colitis: a meta-analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:1562-1567.

64.Senok AC, Verstraelen H, Temmerman M, et al. Probiotics for the treatment of bacterial vaginosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(4):CD006289.

65.McFarland LV, Goh S. Are probiotics and prebiotics effective in the prevention of travellers’ diarrhea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2019;27:11-19.

66.Ebell MH, Siwek J, Weiss BD, et al. Strength of recommenda- tion taxonomy (SORT): a patient-centered approach to grad- ing evidence in the medical literature. Am Fam Phys. 2004;69: 548-556.

67.Panigrahi P, Parida S, Nanda NC, et al. A randomized synbi- otic trial to prevent sepsis among infants in rural India. Nature. 2017;548:407-412.

68.Howick J, Chalmers I, Glasziou P, et al. Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine Levels of Evidence. www.cebm. net/2016/05/ocebm-levels-of-evidence/2011. Accessed March 25, 2020.

69.World Gastroenterology Organisation. WGO practice guideline— probiotics and prebiotics. 2017. www.worldgastroenterology. org/guidelines/global-guidelines/probiotics-and-prebiotics. Accessed March 25, 2020.

70.Szajewska H, Canani RB, Guarino A, et al. Probiotics for the pre- vention of antibiotic-associated diarrhea in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016;62:495-506.

71.Szajewska H, Guarino A, Hojsak I, et al. Use of probiotics for management of acute gastroenteritis: a position paper by the ESPGHAN Working Group for Probiotics and Prebiotics. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014;58:531-539.

72.O’Toole PW, Marchesi JR, Hill C. Next-generation probiotics: the spectrum from probiotics to live biotherapeutics. Nat Microbiol. 2017;2:17057.

73.John GK, Wang L, Nanavati J, et al. Dietary alteration of the gut microbiome and its impact on weight and fat mass: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Genes (Basel). 2018;9. pii:E167.

74.Sherwin E, Dinan TG, Cryan JF. Recent developments in under- standing the role of the gut microbiota in brain health and dis- ease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2018;1420:5-25.

75.Skokovic-Sunjic D. Clinical guide to probiotic products available in USA. 2020. www.usprobioticguide.com. Accessed March 25, 2020.

原文链接:https://www.mdedge.com/familymedicine/article/220474/preventive-care/probiotics-tx-resource-primary-care

作者|Daniel J. Merenstein, Mary Ellen Sanders和Daniel J. Tancredi

编译|C。

审校|617